Systems Thinking — What is it all about?

A small introduction to complexity, the purpose of thinking in systems and the art of building system maps.

With the increase of social and ecological challenges, the need for new ways of thinking and acting arose. More and more people started talking about systems change, integrative approaches or holistic mindsets. But what does the systems thinking really mean? How does it help with complex challenges and how can we make it applicable to our work?

A Dynamic World

“Everything flows.” — “Nothing stands still.” — ”You could not step twice into the same river; for other waters are ever flowing on to you.” (Heraclitus, 500 B.C.)

The world around us is anything but static. It is a dynamic web of elements constantly moving and nothing suddenly appears out of nowhere. All events that we hear in the news or read in the newspapers have a background story, a development that unfolded over time (mostly through reinforcing loops) and lead us to the particular situation we consider worthy for news.

These events are the tip of the iceberg. If we want to understand and use information as a basis for our decisions we need to look for the patterns. A great example is the reporting of the Covid virus. In the beginning of the pandemic, most media sources focused on the total number of infected people in a given region. By now, we see curves everywhere and the number of new infections has become the leading benchmark. This allows us to see beyond the momentary snapshot and understand in what direction we’re heading. #flattenthecurve became the epitome of the evolved dynamic perspective.

For most dynamics, we developed very successful heuristics. We sense the change of temperature in the shower and adjust it by turning the faucet. Even in more complicated situations as driving a car or catching a high-flying ball, we learned to succeed by constantly adapting our (re-)actions to the observations of the dynamic environment. However, all of this becomes a bit more challenging when we add complexity to the mix.

A Complex World

“Does the Flap of A Butterfly’s Wings in Brazil Set Off a Tornado in Texas?” (Edward Lorenz, 1972)

Complexity arises when there is a high number of interdependent factors in the system leading to confusing and seemingly chaotic behavior. While we learned to control complicated systems by experimenting and adapting, increased complexity hinders our ability to derive lessons from our actions. This is because in complex systems effects are decoupled from their causes in time and space (Forrester, 1971). Burning fossil fuels does not immediately change the climate and lead to environmental damage; so we continue doing it and building industries upon it. Optimizing hospital operations might ease the expenses in the short-term but decreases the resilience of whole societies in times of (pandemic) crises.

It is impossible to predict the future development of complex systems — let alone control their behavior. But they are not as chaotic as they might seem. Even the most chaotic systems follow underlying patterns emerging from order-generating rules (Burnes, 2005). A flap of a butterfly might hypothetically lead to the occurrence of a tornado but only if it meets the right conditions that reinforce its energy in intensity and distance. Observing dynamic patterns as they present themselves and understanding the interdependencies within a system can help us to sense the underlying rules and anticipate the consequences of our actions. Our understanding will never be perfect but it will help us to learn from the past and — at the very least — prevents us from making the same mistake twice.

Unfortunately, there seems to be an imbalance between the prevalence of complexity and our collective skills to understand it. While the World Economic Forum (2016) identified Complex Problem Solving as one of the most important skills to have, an evaluation by the OECD (2017) of public administrations across the European Union coined the term of the complexity gap — the disconnect between the degree of complexity these institutions face and the level of institutional capacities they have to successfully work with it.

Looking at the World through a System Lens

“Systems thinking is a discipline for seeing wholes. It is a framework for seeing interrelationships rather than things, for seeing ‘patterns of change’ rather than ‘static snapshots.” (Peter Senge, 1994)

In Systems Thinking, we are applying mindsets, methods and tools that can help us to develop a better understanding of the dynamic complexity that lies within systems. This helps us to anticipate future developments, identify leverage points and design promising interventions to nudge the system towards our vision for a more sustainable state.

The iceberg analogy is a great visualization for the system lens. We aim to look beneath the single events on the surface to unveil the trends over time. We also call these trends patterns or system behavior. Then, we dive deeper to discover the causal structure between interdependent factors that lead to the behavior of the system. Below these causal structures lie the hidden creatures of the deep sea: our beliefs, values and deep-rooted assumptions that influence so much of our doing but often stay well hidden from our view and the view of others.

The iceberg analogy of Systems Thinking: While we mostly hear about the events on the surface, understanding a complex systems requires a deep dive into the patterns, structures and mental models to initiate systemic transformation.

Systems Thinking aims to help us handling complex environments in three distinct ways:

1) System Thinking provides a set of analytical tools that support us making sense of the presented complexity. These tools help us in uncovering the patterns and structures below the surface and how they impact each other. With the tools we aim to build a “virtual world” — a simplified representation of the real world that is simple enough to be grasped by our minds and detailed enough to inform decision-making. They allow us to anticipate future trajectories of the system and to develop systemic theories of change assessing the potential (unintended) impacts of interventions.

2) Systems Thinking provides the artifacts and processes to develop a co-understanding among stakeholders. Despite the rise of data collection and analysis, the majority of knowledge how a system functions and how decisions are made lie within the minds of the actors in the system. Facilitated workshops allow stakeholders to share their stories from the system and integrate their perspectives into a larger picture. The tools fulfill their second purpose as “boundary objects”. Just like a geographical map for a group of travelers, they provide a physical object that people gather around and point to different spots to make sure everyone has a common understanding.

3) Systems Thinking encourages a shift of mindset in how we see and experience the world. Being aware of the complexity around us and our limitations in cognitive capacity to capture all of it, brings — almost automatically — a certain humbleness in our thinking and acting. Decision-making becomes less of a heroic story of individual leadership but more of an ability to listen, to connect, to follow and to foster collective intelligence. We have to become “system learners” making our thinking explicit, constantly challenging our worldviews and listening deeply to the system and the actors within it.

System Mapping

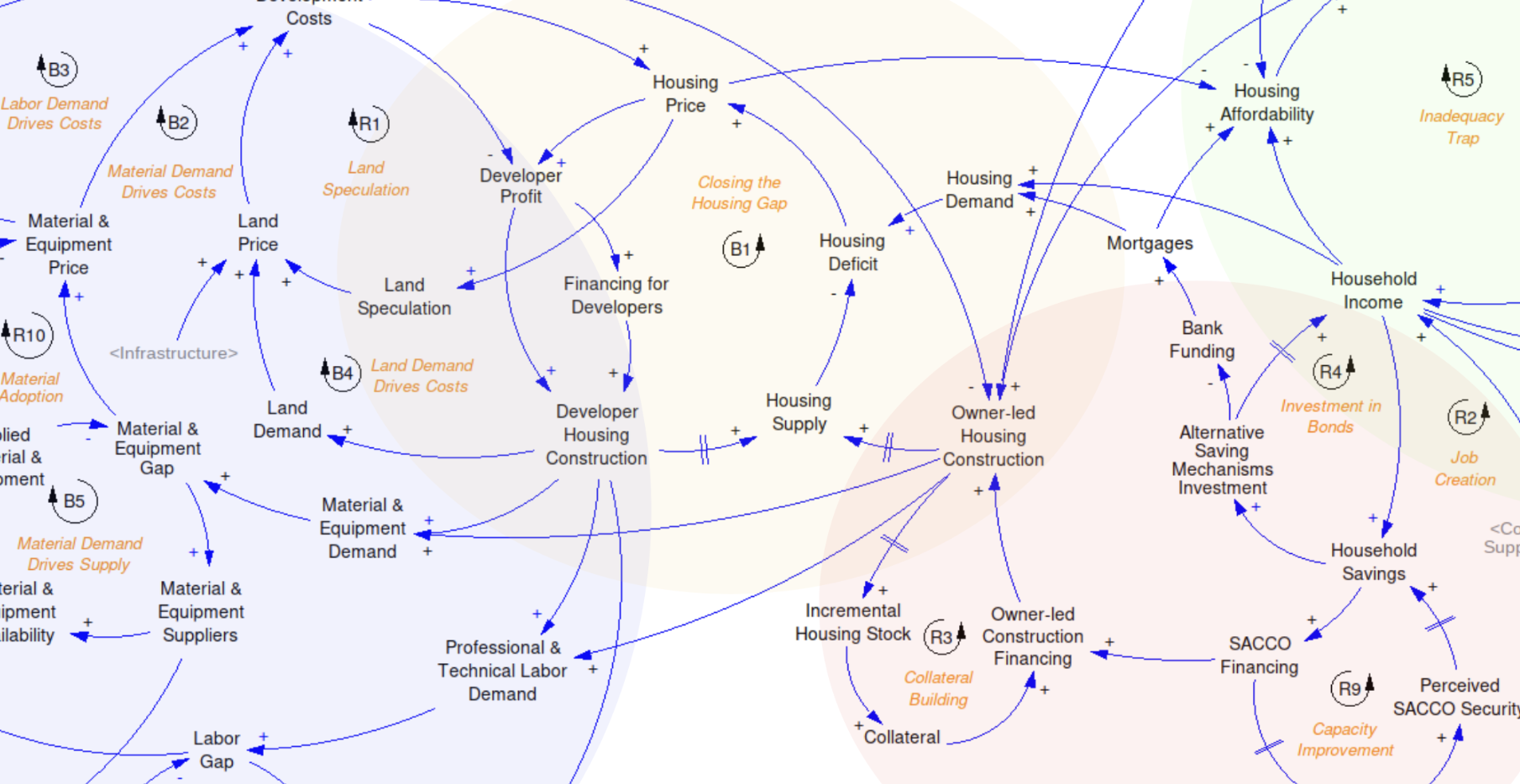

A very popular and powerful tool is the System Map. A System Map — or Causal Loop Diagram (CLD) — is a tool to visualize the causal structure of a system. The map depicts the variables and the causal links between them to identify feedback loops and delays that help us make sense of the dynamics of a complex system.

System Maps actually share many similarities to common geographical maps. We use the System Map to orient ourselves and bring structure to a sometimes overwhelming amount of information. (System) Maps are most effective when they bring people together. Leaning over the same map, naming the elements and working together on the structure, the actors within the system develop a shared understanding beyond their functional silos. They can anticipate their current position, the trajectory into the future and interventions that helps them to navigate towards their guiding star.

What drives adequate housing? A System Map depicting the factors and causal relations related to adequate urban housing in an East-African country. The map was developed together with a regional NGO and diverse stakeholders within the housing sector to guide the development of strategic interventions.

Creating a comprehensive System Map for policy support is a participatory endeavour which requires time for discussion and time for reflection. The map does not aim to represent a complete system but focusing on the causal logic behind a specific challenge. A problem statement or research question is hence an essential input to guide the mapping process.

Feedback loops are one of the key structural elements that help us to understand behavior. Reinforcing loops are closed causal chains which reinforce an initial impulse. Reinforcing loops can go both ways: They can be the drivers of virtuous change but can also lead to dangerous vicious cycles. The second kind of feedback are balancing loops. They stabilize a system bringing a balance to its behavior but can also hinder much-needed change. Each feedback loop tells a story of the system and understanding their interactions is key to understand behavior and identify leverage points for intervention.

Interaction of Feedback Loops: Two reinforcing loops (Infection spread, poverty trap) and their corresponding balancing loops (No more people to infect, Educational policies).

The System Map is a model and just like any other model it is a simplification of reality. The question, though, is not whether to use a model or not. We always rely on models as all our decisions are based on a mental, incomplete understanding of reality (Forrester, 1961). These mental models are difficult to grasp and we only communicate them partially and indirectly. The System Map makes these assumptions explicit and gives people the chance to learn from each other, challenge each other and build an integrated model together.

In preparation for past workshops, we developed some examples for System Maps. These might provide a good starting point to see how a System Map integrates and tells the stories of the system:

The Fishermen of Kiribati: When good intentions backfire.

How Paris meets Climate Change: The balancing loops that slow mobility transformation.

To get a better idea how System Mapping looks in practice, we published an article about our recent project experience in Peru. Together with UNDP Peru, we developed a participatory System Map to understand, discuss and improve deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon — System Mapping in Action: Deforestation in Peru.

Embarking on the Systems Journey

“The only true voyage of discovery […] would be not to visit strange lands but to possess other eyes, to behold the universe through the eyes of another, of a hundred others, to behold the hundred universes that each of them beholds, that each of them is.” (Marcel Proust, 1923)

Our world is dynamic, complex and sometimes overwhelming. Understanding complexity is not a sprint but a long and windy road of continuous discovery. Systems Thinking does not solve the complexity but it equips us with tools, methods and mindsets to see our environment through new lenses and to deepen our engagement with the people around us. Only if we cooperate with open hands, listen with open hearts and learn with open minds we can take collective action for the long-term health and sustainability of our complex and fascinating world.

References

(… and great sources for further exploration)

Burnes, B. (2005). Complexity Theories and Organizational Change.

Forrester, J. W. (1971). Counterintuitive Behavior of Social Systems.

Lorenz, E. (1972). Predictability.

OECD (2017). From Transactional to Strategic: Systems Approaches to Public Service Challenges.

Senge, P. (1994). The Fifth Discipline: the Art and Practice of the Learning Organization.

World Economic Forum (2016). The Future of Jobs: Employment, Skills and Workforce Strategy for the Fourth Industrial Revolution.